“The risk of being involved in a serious car accident increases significantly when the driver’s blood alcohol range substantially exceeds the basic legal limit,” outlines a 2023 NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research report on sentencing high range prescribed concentration of alcohol drivers.

“In particular”, underscored the BOCSAR researchers David Saffron and Marilyn Chilvers, “the crash risk of a driver whose blood alcohol concentration reaches the high range (0.15 grams per 100 millilitres) prescribed concentration of alcohol is 25 times that associated with a non-drinker.”

This understanding leads to the steeply legislated punishment for this often-deadly traffic crime, which carries an automatic licence disqualification of up to 3 years for a first offence and for second or subsequent breaches of the law, up to 5 years without a licence to drive in this state can apply.

Although mandatory interlock laws have been in place for the offence of high range drink driving since 2015, and were then applied to other such offences three years later, which have had the effect of lowering applicable licence disqualification periods, when applied in response to drink driving.

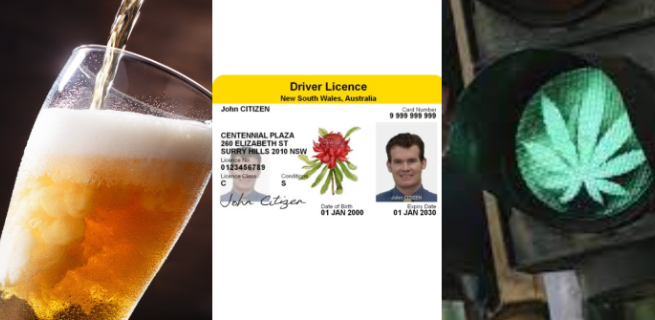

Drink driving law nationwide carries a sliding scale of PCA crimes, with penalties increasing in severity with the rise in blood alcohol concentration (BAC).

And the 1982 established NSW random breath testing (RBT) for alcohol regime has since turned “a common practice” into “highly stigmatised criminal behaviour”.

The success of RBT is its basis in scientifically proven BAC levels, which, while inconvenient for drink drivers, are clearly justified by the science.

However, the 2007-imposed NSW drug driving regime has no legitimacy, as it relies on dodgy law and the false assumption that it’s akin to RBT.

Drinking and driving in NSW

Due to a request by the then NSW attorney general for a guideline judgement on high range drink driving law, a five justice bench of the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal delivered 8 September 2004 findings, which saw the bench determine not to fulfill the application, as the guideline was unwarranted.

The justices outlined that while, with the addition of RBT scientific data, the initially established in 1968 high-range PCA offence, which was then under section 4E of the Motor Traffic Act 1999 (NSW), has demonised drink driving, about a third of Local Court time in 2004 was still being consumed by it.

Back in 1968, a $400 fine and up to 6 months prison applied, and a court could impose any period of licence disqualification.

While in 1999, traffic law was divided up under several newly legislated Acts, with penalties having increased over the interim years, along with a scale of different levels of impairment then applying.

Today, the Road Safety Act 2013 (NSW) contains the relevant offences relating to both drink driving and drug driving in this state. And section 110 of the Act carries the offence of driving with the presence of a prescribed concentration of alcohol in a person’s breath or blood.

Five ranges of drink driving offence are now contained in section 110. Low range PCA is from 0.05 to less than 0.08 BAC. Middle range drink driving is more than 0.08 but under 0.15. And high range PCA is over 0.15, while there are novice range and special range drink driving levels that apply to new drivers.

Driver licence disqualification

Then NSWCCA Justice Roderick Howie explained in the 2004 determination that “licence disqualification is… a significant matter and can have… a devastating effect upon a person’s ability to derive income and to function appropriately within the community”.

His Honour added that licence disqualification “is a matter which… must be taken into account by a court when determining what the consequences should be, both penal and otherwise, for a particular offence committed by a particular offender”.

Indeed, the justice further outlined that there was “considerable debate before the court”, as to whether licence disqualification should be considered to be part of the overall sentence, alongside imprisonment and fining, as some thought it not a penalty, whilst others argued that was absurd.

Justice Howie then added that due to the serious consequences that licence disqualification has upon people’s daily lives, if parliament had expected that this would not be taken into account when imposing the other penalties, then “it should have said so in plain and simple terms”.

Drug driving disqualification

Former NSW Magistrate David Heilpern pointed out the 2004 assessment of the seriousness of the impact driver licence disqualification has upon constituents, especially those in regional and rural areas, and the unfairness in relation to drug driving law, during an interview a few weeks back.

Since May 2019, a first-time drug driving offence can result in a 3-month licence disqualification period and an on-the-spot fine of $572, which means an offender avoids going to court.

However, if the offender decides to challenge the matter in court, it can result in a fine of $2,200 and a 6-month licence disqualification period. And second or subsequent offences can carry of up to $3,300 fine with a 12-month disqualification time frame applying.

Heilpern told Sydney Criminal Lawyers that the reason behind the imposition of licence disqualification upon those testing positive to drug driving at NSW police roadside testing operations is problematic is due to the failure to have based drug driving law on scientifically proven fact.

And as the current Drive Change campaign lead also explained, drug driving licence disqualification can result in loss of job and then lead onto loss of house. Yet, the system is not proving that these licenced drivers were a danger to road safety at the time they were suspended from driving.

No excuse drug driving

The reason that Drive Change considers NSW drug driving law illegitimate, as do a broader range of community advocates who’ve been pushing for reform to the regime for over a decade, is that while RBT tests drivers for levels of alcohol in the blood, when it comes to drugs it’s based on presence.

Section 111 of the Act outlaws driving with presence of certain drugs (other than alcohol) in oral fluid, blood or urine. And the issue with this offence is that the devices used by NSW police don’t detect levels of the four substances tested for but merely ascertains their presence.

This practice results in people being convicted of drug driving when not intoxicated and, therefore, not posing a risk to road safety.

Indeed, a number of Heilpern rulings are renowned for having acquitted drivers who’d falling foul of the law after having smoked a joint days prior, or due to second hand smoke.

However, the recent February 2004 Narouz decision of the NSWCCA confirmed, in line with the findings of a 2023 case, that drug driving is an absolute offence, meaning that the defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact, that had always applied to this law in the past, no longer does.

This means that if a driver is now charged with drug driving in NSW, there is no defence available to them, despite whether the source of the drugs in their system is known to them. And for this, their licences are then being mandatorily suspended.

“I am critical of the judgement because it is out of touch with the seriousness where people lose their licence,” Heilpern made clear earlier this month.

“And had that been taken into account from a more practical and coalface perspective, then perhaps the decision would have been different.”