The UK High Court of Justice ruled on 10 December last year, that the decision not to permit the extradition of Australian journalist Julian Assange, handed down by District Court Judge Vanessa Baraitser on 4 January 2021, be overturned.

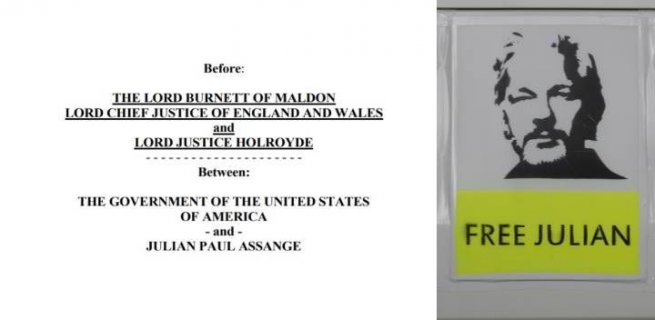

Lord Chief Justice Ian Burnett and Lord Justice Timothy Holroyd made the decision based on two days of hearings that took place in late October.

In their findings, Chief Justice Burnett set out that the details of the WikiLeaks founder’s case is “well-known”. And if extradited, Assange would face “18 counts connected with obtaining and disclosing defence and national security material through the website, primarily in 2009 and 2010”.

The US requested extradition to face these charges in July 2020. At that time, he was being held in London’s Belmarsh prison, after he’d been taken into custody in April the year prior, over a breach of bail.

The sentence for bail breach had since expired, and Assange is currently being remanded on behalf of the US.

Baraitser rejected the US case originally based on the provisions within section 91 of the Extradition Act 2003 (UK), finding that in regard to Assange’s mental health it would be “oppressive” to extradite him, due to the conditions he’d likely be subjected to in the US prison system.

SAMs

The primary judge found that based on past cases, “it would be likely” that Assange would be held in what’s known as special administrative measures (SAMs) – extreme isolation – “both pre- and post-trial”, and considering the Australian’s mental health, the US couldn’t guarantee he wouldn’t suicide.

This was based on evidence presented by neuropsychiatrist Professor Michael Kopelman, which set out that if kept in isolation Assange’s mental state would deteriorate to the point where he’d be at significant risk of taking his own life.

This was further supported by psychiatrist Dr Quentin Deeley, who had diagnosed Assange with autism spectrum disorder and Asperger’s syndrome disorder.

Baraitser rejected evidence to the contrary provided by forensic psychiatrist Dr Nigel Blackwood, who acted on behalf of the US, as he’d spent limited time with the journalist.

Her Honour found that the case satisfied the criteria set out in the 2012 authority Turner versus the US. And she also rejected all six further grounds for extradition the US had submitted to the court.

On appeal

The US appealed the decision to the UK High Court on 27 and 28 October 2021, based on five grounds.

The court allowed the appeal in relation to the fifth. This involved assurances that Assange would not be placed in SAMs, which were provided following the decision not to extradite him in January 2021.

Assange’s legal team submitted that Baraitser was entitled to make her findings based on the evidence, and that the assurances came “too late”, as well as the promises not actually removing “the real risk” of SAMs detention.

Further, the Australian’s lawyers argued that if the assurances are admitted, the case should be remitted to the original judge to personally deliberate upon the decision again.

The assurances

The US provided four assurances within Diplomatic Note no. 74 dated 5 February 2021.

The four assurances involve not placing Assange in either SAMs or the harsh setting within the ADX Florence prison, that if he submitted a successful transfer application to serve his time in Australia, it would be honoured, and that he would receive adequate mental health care whilst in custody.

However, the assurances contain the caveat that the US “retains the power” to send Assange to the supermax ADX facility, “in the event that, after entry of this assurance, he was to commit any future act that then meant he met the test for such designation”.

Assange’s counsel argued that the assurances contradict the previous position of the US that maintained the severity of SAMs had been exaggerated, that the conditional nature of them defeated their purpose, and that they further leave other restrictive detainment options open.

Appeal upheld

The Chief Justice found that the assurances could be accepted during any stage of an extradition case.

And in relation to Assange’s, his legal team had delivered numerous grounds to resist extradition, and the US couldn’t have been expected to provide assurances initially covering every possible outcome.

Indeed, their Honours found that at the point that Baraitser provided a draft of her judgment, she should have also offered the US an opportunity to provide assurances regarding the grounds she finally determined not to extradite the journalist on.

The High Court was satisfied that it could accept the assurances at this “late stage” in the case, as the provision of them was “a solemn undertaking”, which was “offered by one government to another” and “will bind all officials and prosecutors who will deal” with Assange’s case in the future.

In terms of the caveat, their Honours found that “it is difficult to see why extradition should be refused on the basis that Mr Assange might in future act in a way which exposes him to conditions he is anxious to avoid”.

And the decision to uphold the fifth ground relating to the assurances, also entailed upholding the second ground of appeal, which claimed the primary judge had made an error in not providing the US with opportunity to submit the assurances it has since, prior to the handing down of her decision.

Remitted to the lower court

Further consideration was given to the fact that the primary judge accepted Professor Kopelman’s position, despite it being found that in his first report to the court, he had concealed the identity of Assange’s current partner, Stella Moris, as well as the fact that her children are his.

The neuropsychiatrist stated this was due to her existence not having been made public over concerns for her and her child’s safety. Although Kopelman had referred to them clearly in his second court report, once she had gone public.

The two UK High Court justices found that it was open to Baraitser to accept the neuropsychiatrist’s testimony, despite his misleading the court, however the justices made clear that they could not agree that the professor “did not fail in his personal duty”.

And in upholding the two grounds of appeal, the High Court remitted the case back to Judge Baraitser to act as if she had “decided differently” in the first instance, and hand the case over to the UK secretary of state to make the final decision on extradition.

Send him to Australia

Send him home to his family whether it is in the UK or Australia… he needs to be released and those unjust charges must be dropped immediately.